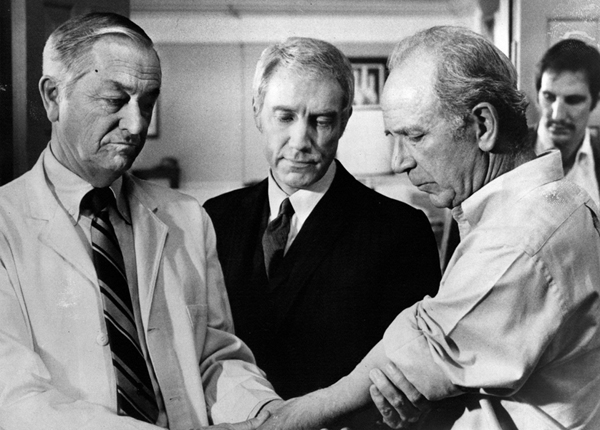

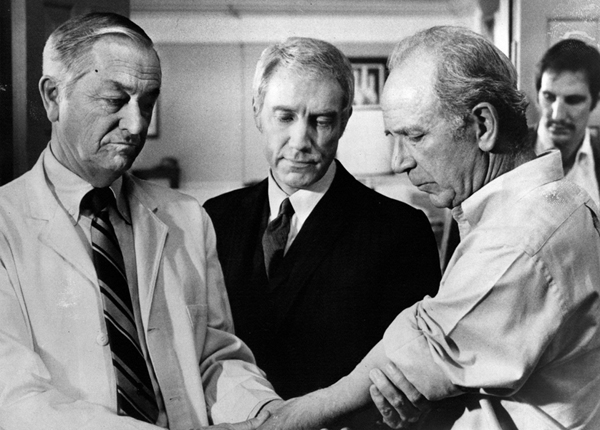

The world’s unlikeliest junkie: Jack Albertson (right) is the heroin-addicted school bus driver in Mankiewicz’s “Go Get ’Em, Tiger,” with Robert Young (left) as Marcus Welby and William Smithers as the school board bureaucrat.

Born January 20, 1922, Berlin, Germany.

Videography

As writer

Studio One: “The Man Who Had Influence” (story only) (5/29/50)

Schlitz Playhouse of Stars: “Never Wave at a WAC” (10/19/51)

Studio One: “The Edge of Evil” (from a Doris Miles Disney story) (3/23/53)

Lux Video Theatre: “The Nine-Penny Dream” (8/4/55)

Star Stage: “On Trial” (9/23/55)

On Trial/The Joseph Cotten Show (various episodes, 1956-1957)

Playhouse 90: “The Last Tycoon” (from the F. Scott Fitzgerald novel) (3/14/57)

Playhouse 90: “The Male Animal” (from the Thurber/Nugent play) (3/13/58)

Kraft Television Theatre: “All the King’s Men” (from the novel) (5/14/58 & 5/21/58)

One Step Beyond: “Epilogue” (2/24/59) [DVD]

One Step Beyond: “The Navigator” (4/14/59)

One Step Beyond: “Front Runner” (6/5/59) [DVD]

One Step Beyond: “The Explorer” (3/15/60)

One Step Beyond: “House of the Dead” (6/7/60)

One Step Beyond: “The Last Round” (1/10/61) [DVD]

Armstrong Circle Theatre: “Legend of Murder: The Untold Story of Lizzie Borden”

(10/11/61)

Bus Stop: “The Resurrection of Annie Ahearn” (co-teleplay) (10/15/61)

General Electric Theatre: “Go Fight City Hall” (1/28/62)

Armstrong Circle Theatre: “Journey to Oblivion” (6/6/62)

DuPont Show of the Week: “The Interrogator” (9/23/62)

Armstrong Circle Theatre: “Invitation to Treason” (1/2/63)

Armstrong Circle Theatre: “Secret Document X256” (6/5/63)

Profiles in Courage: “Governor John M. Slaton” (12/20/64)

Profiles in Courage: “General Alexander William Doniphan” (1/17/65)

Profiles in Courage: “Frederick Douglass” (1/31/65)

Who Has Seen the Wind? (telefilm) (3/19/65)

Profiles in Courage: “George W. Norris” (3/28/65)

Profiles in Courage: “Judge Ben B. Lindsey” (4/25/65)

Profiles in Courage: “Thomas Corwin” (5/9/65)

The Trials of O’Brien: “The 10-Foot, 6-Inch Pole” (1/14/66)

Hawk: “Thanks For the Honeymoon” (teleplay only) (9/22/66)

Hawk: “How Close Can You Get?” (teleplay only) (10/27/66)

Star Trek: “Court Martial” (story and co-teleplay) (2/2/67) [DVD]

Ironside (pilot telefilm) (teleplay only) (3/28/67)

Ironside: “Message From Beyond” (9/14/67) [DVD]

Ironside: “The Leaf in the Forest” (9/21/67) [DVD]

Ironside: “Dead Man’s Tale” (story and co-teleplay) (9/28/67) [DVD]

Ironside: “Split Second to an Epitaph” (two hours) (co-teleplay) (9/26/68) [DVD]

Mannix: “The Girl Who Came in With the Tide” (co-teleplay) (2/1/69)

Marcus Welby MD (telefilm) (teleplay only) (3/26/69)

Marcus Welby MD: “Go Get ’Em, Tiger” (2/10/70)

Sarge (pilot telefilm) (2/22/71)

The Bait (telefilm; from a Dorothy Uhnak novel) (3/13/73) [with Gordon Cotler]

McMillan and Wife: “Death of a Monster . . . Birth of a Legend” (9/30/73) [with Gordon Cotler]

McMillan and Wife: “The Man Without a Face” (1/6/74) [with Gordon Cotler]

Lanigan’s Rabbi (pilot telefilm; from a Harry Kemelman novel) (6/17/76) [with Gordon Cotler]

McMillan: “Philip’s Game” (teleplay only) (1/23/77) [with Gordon Cotler]

Lanigan’s Rabbi: “Corpse of the Year” (1/27/77) [with Gordon Cotler]

Lanigan’s Rabbi: “The Cadaver in the Clutter” (teleplay only) (3/17/77) [with Gordon Cotler]

Lanigan’s Rabbi: “Say It Ain’t So, Chief” (co-teleplay) (4/14/77) [with Gordon Cotler]

Rosetti and Ryan: Men Who Love Women (pilot telefilm) (co-teleplay) (5/19/77) [with

Gordon Cotler]

Sanctuary of Fear (telefilm) (4/23/79) [with Gordon Cotler]

Hart to Hart: “The Harts at High Noon” (11/11/82)

Hart to Hart: “Hart’s Desire” (co-teleplay) (11/16/82)

I Want to Live (telefilm; from Mankiewicz’ and Nelson Gidding’s 1958 screenplay)

(5/9/83) [with Gordon Cotler]

MacGyver: “To Be a Man” (3/5/86) [DVD]

The Marshal: “Bounty Hunter” (3/11/95)

The Marshal: “Time Off For Clever Behavior” (co-teleplay) (12/25/95)

As executive script consultant

Hart to Hart (1982-1983?)

Feature Films (as writer) : Fast Company (1953); The Big Moment (United Jewish Appeal short) (1954); Trial (1955); House of Numbers (1957); I Want to Live (1958); The Chapman Report (1962)

Novels: See How They Run (1951); Trial (1955); It Only Hurts Once (1966)

They called them the “Sons of the Pioneers,” punning on the name of the country-western group prominent during the thirties and forties. Sons of the Hollywood pioneers, that is: young men who grew up on the orange tree-lined streets of Los Angeles as their fathers (and occasionally mothers) laid the groundwork of the motion picture industry. Acclimated to the movie business from childhood, many of them naturally followed their parents into it. Budd Schulberg was probably the most famous of them, not because he won an Oscar for On the Waterfront or because his father was the deposed head of Paramount in the twenties, but because his first writing effort of note, the novel What Makes Sammy Run?, was a gossipy expose of Hollywood venality whose characters were thinly disguised takes on real-life figures from the thirties studio community.

Mostly in their twenties when television arrived, these men often spent their careers working behind the small screen. It was their chance to make up an entertainment medium as they went along, just as their fathers had done. Christopher Knopf, son of the MGM producer Edwin Knopf, became an award-winning writer for The Dick Powell Show and Cimarron Strip. John Meredyth Lucas, son of writer Bess Meredyth and stepson of Casablanca director Michael Curtiz, produced Ben Casey and Star Trek. Harry O producer Robert Dozier, son of William Dozier, was television’s equivalent of Schulberg, coming to prominence with a Climax teleplay about his tempestuous relationship with his father.

All of this is by way of noting that when the writer Don M. Mankiewicz’s name appears on a television screen, the knowledgeable viewer is likely to wonder if he is related to Herman Mankiewicz, the legendary screenwriter of Citizen Kane. Or Joseph Mankiewicz, the famously literate writer-director of All About Eve and A Letter to Three Wives. In both cases the answer is yes: Don is the son of Herman, the nephew of Joseph. His younger cousins, Joseph’s children, have also had noteworthy careers in the industry: Chris Mankiewicz as a producer, Tom Mankiewicz as a screenwriter (of several James Bond films) and story consultant (on Hart to Hart), and Ben Mankiewicz as a host on the Turner Classic Movies channel.

Amid that dynasty, Don Mankiewicz remains a surprisingly little-known figure, a resource underutilized by historians and, more to the point, a talented writer who wielded a distinctive voice. Beginning as a live TV dramatist, Mankiewicz specialized in stories about the rituals of law and politics, subjects of such great interest to him that for a time he maintained a parallel career as a public servant. Mankiewicz liked to craft scripts for shows like On Trial and Armstrong Circle Theatre out of stranger-than-fiction incidents from the back pages of the newspaper, or by turning his imagination toward the ramifications of some arcane point of law. His work possessed a specificity and an attention to detail rare in the early days of television. It was natural that producer John Newland, in focusing his anthology of the paranormal One Step Beyond on documented incidents, would recruit Mankiewicz as one of that show’s primary writers.

Mankiewicz had a gift for rich dialogue as well. John Frankenheimer, who directed Mankiewicz’s television adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s unfinished novel The Great Tycoon, remembered decades later that, “some of the best dialogue in that show is not Fitzgerald, it’s Don Mankiewicz.”1 Above all, Mankiewicz possessed a skill for getting to the heart of the matter, a way of conveying complex emotional or intellectual shifts in his characters through spare, precise lines.

In this scene from his Marcus Welby script “Go Get ’Em Tiger,” for instance, Dr. Welby scolds his younger colleague for what he sees as a lapse in judgment:

KILEY: I had to help him, even if it meant sticking my neck out. Understand?

WELBY: I might, if it had helped him, but it didn’t – that’s the point.

KILEY: Well, I didn’t break any law.

WELBY: Law? I’m talking about the greatest medical crime of all: stupidity. Double-dyed, compound stupidity. Didn’t you know they’d check the man’s record?

KILEY: I didn’t think about it.

WELBY: You didn’t want to think about it.

KILEY: There’s a question of a confidential relationship between doctor and patient.

WELBY: Oh, baloney. As we used to say in the olden days. If there’s anything more pitiful than a lawyer practicing medicine, it’s a doctor practicing law. That exam was paid for by the school, and it was your job to record any material –

KILEY: I don’t believe a man’s former addiction is material.

WELBY: Stop it! Stop the defenses and the technicalities. Now look at what’s happened. Chambers doesn’t have a job, and Howe wants your head on a pike. And he may get it. Now, why didn’t you talk to me about this in the first place? Why all the secrecy?

KILEY: I didn’t think it was fair. It was my problem.

WELBY: And you knew in your heart that what you were doing wouldn’t work, and it was wrong besides. But you didn’t want to ask me, because you knew I’d tell you exactly that. You were wrong, Steve. Dead wrong. Admit it. No excuses, no defenses, no evasions, no if ands or buts. You were wrong. Weren’t you?

KILEY: Yes. I was wrong. What I did, how I did it – all wrong.

WELBY: Now that you’ve admitted your mistake, let’s you and I try to figure out how to correct it.

Kiley’s decision to help a school bus driver who is recovering from heroin addiction (Jack Albertson) by omitting his drug use from a medical report earns the audience’s sympathy, but Mankiewicz insists on the point that Kiley’s good intentions do not excuse a greater social responsibility. Shrewdly ascribing this less popular point of view to a character (Welby) who was already established as a voice of tough wisdom, Mankiewicz makes his case as neatly as a mathematician executing a proof.

The world’s unlikeliest junkie: Jack Albertson (right) is the heroin-addicted school bus driver in Mankiewicz’s “Go Get ’Em, Tiger,” with Robert Young (left) as Marcus Welby and William Smithers as the school board bureaucrat.

The most visible writing of Mankiewicz’s New York period was for Profiles in Courage, the ambitious historical anthology based on John F. Kennedy’s bestselling book. (Initially dumped in the Sunday afternoon ghetto of little-seen cultural programming, Profiles had a long afterlife in public schools’ sixteen-millimeter libraries of educational films.) Mankiewicz’ take on the Kennedy book was narrow and typically incisive. Concerned that the show could devolve into an array of simplistic stories of achievement culled from the lives of great men, Mankiewicz wrote instead about individuals who had sacrificed their reputations or careers to defend an unpopular stance. “Thomas Corwin” was a senator who opposed President Polk’s declaration of the Mexican War; Georgia’s “Governor John M. Slaton” defied violent anti-semitism to pardon Leo Frank, a man convicted unjustly in an infamous murder case. In his look at “Frederick Douglass,” Mankiewicz focused on the famous abolitionist’s decision to risk his own liberty (he was a fugitive slave who could be legally returned to bondage in the South) in order to speak out against slavery.

Mankiewicz’s most unusual Profile was a segment that appeared to contradict his distaste for simple, uplifting tales. “Judge Ben B. Lindsey” examined a turn-of-the-century Denver judge who helped to establish juvenile courts and fought to outlaw child labor. The first half of Mankiewicz’s script portrays Lindsey (a terrific George Grizzard) as an earnest do-gooder angered by minimum sentencing laws which require him to punish children who steal coal to warm their homes as hardened criminals. Lindsey enlists the aid of an unexpectedly compassionate railroad baron (David Brian, perfectly cast) to establish work programs that will curb juvenile delinquency. But just when Judge Lindsey starts to look like a Disney-styled hero – a band of picturesque urchins follows him through the streets at one point – Mankiewicz plunges the viewer into reality. Lindsey, flush with victory, announces that he will take on illegal gambling dens next. The railroad magnate’s face hardens. He orders Lindsey to quit while he’s ahead. Lindsey realizes that big business has used him to make small, cost-efficient social gains that look good in the press, but that when he threatens serious capital, the political-industrial machine shuts him down. Lindsey tries to outmaneuver his opponents by pressuring the police to raid known gambling dens. In the raids, one of the boys Lindsey helped to divert from prison is killed.

Subtly, Mankiewicz questions the hubris of his protagonist. He offers the sophisticated argument that judicial activism – Lindsey’s willingness to interpret the law counter to its obvious intent in order to achieve the result he desires – will have dire consequences no matter how honorable its intent. And, of course, Mankiewicz’s cynical script indicts the institutionalized corruption that Lindsey encounters, suggesting that it is an inescapable byproduct of any capitalist society in which financial profit is cherished above anything else.

By the time Profiles in Courage ceased production, so had most of the other gritty New York dramas that were keeping live television’s last holdouts afloat on the east coast. In 1966, Mankiewicz moved to Hollywood and quickly established a foothold in mainstream television, writing the telefilms that served as pilots for both Ironside and Marcus Welby, M.D. By today’s standards, Mankiewicz would probably possess a sole or at least a shared “created by” credit on both series. Offered a chance to produce Ironside, Mankiewicz said no, opting not to attach himself to a single series. He continued to turn out episodic scripts and television movies, eventually taking on his old college classmate, the novelist Gordon Cotler, as a writing partner.2

Though he adapted to the generic requirements of detective and doctor shows, Mankiewicz remained attentive to his earlier obsessions. In “Go Get ’Em, Tiger,” the climax takes the form of a school board meeting in which Welby, the board members, and the student body engage in a socratic debate over the usefulness of former addicts in dissuading drug use among the young. As he had done in his Star Trek episode, “Court Martial,” which speculated on the nature of the legal process in the twenty-third century, Mankiewicz bent Marcus Welby’s format toward a dialectic in which the possible resolutions of his scenario are scrutinized and then accepted or rejected.

If those descriptions of his output make Mankiewicz sound like the driest sort of intellectual, rest assured that other assignments brought out an earthier, more playful side. “The Leaf in the Forest” was a serial killer story with a lurid paperback flavor and a tricky twist ending, and another of his Ironsides took one of Mankiewicz’s own favorite hangouts, the racetrack, for its milieu.

It was this aspect of Mankiewicz, this cheerful enthusiasm for the seedy and the strange, that I thought of when I met him for a long, late lunch at the venerable Canter’s Deli in West Hollywood. Maybe it was just the stuck-in-the-seventies decor in the darkened, empty back room of Canter’s, but the laid-back Mankiewicz seemed much more the sort of character you’d expect to find at the track than in the committee meetings and union events where he’d spent much of his professional life. A droll raconteur, Mankiewicz encouraged a view of TV writing as an easy way to make a comfortable living or, at least, a less colorful arena in which to spend one’s life than politics or law. Inevitably, our conversation strayed from Mankiewicz’s own career and into some fascinating tangents of Hollywood lore and political scandal.

When did you first start writing?

When I went into the army I was partway through law school – as a matter of fact, I’m still on military leave from Columbia law school – and then I wrote a short story that I sent to the New Yorker and they bought it. They paid me, I think, $175, and it took me about an hour to write it. So I said, “$175? Jesus Christ.” I’d already noticed that my father seemed to live reasonably well, seemed to have money, didn’t fall down exhausted from doing any heavy lifting. So I decided that’s what I would do.

Then I got a letter from a guy named Jack Schoenbrun, who was an agent, offering to represent me. He was a crook, as it turned out. I wrote some kind of a piece for him that he sold to an Australian magazine. That was about gambling, I think.

I did radio. I did gags for Robert Q. Lewis, who was a comedian at that time. He paid me $25 a page. If I typed pretty big and filled the page pretty easily, I could make $50 a week there.

Were you living in New York during the live television era?

Yes. I came out here [to Los Angeles] for a while and got married, and then we went back to New York. I lived in the city. I really don’t know how I got into television. Somebody must have suggested it.

In 1951 Studio One adapted a short story of yours called “The Man Who Had Influence.”

Oh, did they buy that? That was a Saturday Evening Post story, I think. But I didn’t adapt it. I had completely forgotten that.

The first credit of yours that I know about was on “Never Wave at a WAC,” a Schlitz Playhouse of Stars.

All I remember is that it was set in a Catskills hotel and the people were stealing [from the hotel], and I invented the notion that [there was] some pretext for opening all the bags – that a jewel thief was loose and that everybody’s bag would have to be checked, so they didn’t take the towels. There wasn’t any jewel thief. This is kind of slight to sustain [for] an hour, but it worked. It was not completely original, I don’t think, and I forget who was in it.3

Felix Jackson was the producer.4 He was a fairly well-known producer of fluffy musicals. He was a friend of my father’s and maybe he called me and lured me into this, or maybe I saw something in the paper about it. I used to sell myself more readily than I do now. I got to be shy over the course of the years.

Another thing that kind of impeded me is that I was a politician all this time. I mean organization: knock on the door, carry the petitions, raise the money, and all that stuff. That started around 1948, then we moved to Nassau County. We finally turned Nassau County Democratic, but before we turned it Democratic I ran for the assembly in ’52 and I lost.

You ran on the Democratic ticket?

Yeah, a Democrat and Liberal. And the Times thought it was kind of unusual that somebody with any name at all would run in Nassau County, where the Democrats had not won since Lincoln. We beat Lincoln, and we used to say if he ran again we could beat him again.

In ’50, my brother Frank had run out here and he won his primary, which was very unusual, for a Democrat to win the Democratic primary. They had cross-filing in those days. He was the first Democrat to get on the ballot as a Democrat. Then, of course, he lost. So I figured that seemed like fun, so I tried it. I didn’t really want to run for the Assembly. All I wanted to be was a committeeman, I wanted to run my district. I went to the county leader. He was really understanding what was going on; he looked at his book and said, “Well, we already have two committeemen in your district. That’s what we’re supposed to have – one man and one woman. So I can’t make you a committeeman. How about you run for the Assembly?” So I said, “Okay, I’ll do that.”

I ran a fairly good race. It was reasonably close. It was close enough so that the bulldog papers did not concede it, and in the morning the Times put out the story that said that I was swept away in the Eisenhower landslide. So I called my father, who had put up most of the money for this, although $500 was what it cost me to run. That was a high price for an Assembly [race] – for that I had a storefront, newspaper ads, and god knows what all.

So I read him the Times piece, and he said, “Well, you know, that election, Eisenhower won 52 to 48.” He said, “They don’t make landslides like they used to.” And it’s true. Now today we read that Bush won in a landslide that was 51 to 49.

So that did take up a certain amount of my time. ’66 was the only time it stopped me [from writing] completely. I ran statewide for delegate at large to the state constitutional convention in New York, and I won. That meant I had to be in Albany for half a year. But except for that there wasn’t any great interference [by] politics. My brother would’ve been a good lawyer, and he was a pretty good writer. He wrote a couple of good non-fiction books, but he also got distracted by politics, and now he does only politics.5

Did you really see a career for yourself in politics?

Yes, and I should have had it. I really wanted to be a congressman. That’s what I decided when I was about fifteen. I reached the point in ’64 when I was offered the nomination by the county leader for U.S. Congressman from the 3rd Congressional District. That included the North Shore of Long Island, which was fifty percent Democratic, almost. I could not lose, because this was Johnson against Goldwater; he was going to carry it two to one, which he did. Then I had to turn it down because I was getting a divorce from my wife, and she said that if I ran she would – I knew that she knew I was not entirely faithful, but I didn’t know that she was making a book on it with detectives and all that stuff. She was going to give that to my opponent if I ran, who was Steven Derounian, who was a fear artist. He’s the fellow from the picture Quiz Show, the one [on the Congressional committee] that will not accept poor Charlie Van Doren’s explanation [about his participation in the rigging of quiz programs]. Van Doren would have fooled the whole Congress but Derounian says, no, this is just a liar trying to cover up his tracks. All the others were willing to accept that Van Doren was sorry that it happened.

That sounds like something out of Gore Vidal’s The Best Man.

Yes, it really was, it was that kind of a situation.

Did you also like to write about politics?

Yeah, I did a very good two-part [adaptation of] “All the King’s Men” for Kraft, with a celebrated director, Sidney Lumet.

Live?

Yes. Neville Brand [who played the Huey Long character] was a good actor, but what he’s famous for is that he was blacklisted at Universal. He was a drunk and he pissed on a tour bus filled with tourists. He didn’t work at Universal after that.

He must have been great as that Huey Long character.

He was. He was superb.

What little technique I learned about adaptation was when I did Trial with Charlie Schnee, who was the producer.6 He was a writer himself, in fact an Oscar winner, and he taught me how you do it. It doesn’t work any more, but he taught me the technique that you’d divide the play into sequences, and each sequence ends with a dissolve. None of this is true any more, but I used that . . . . That was really the only instruction I had; the rest I just sort of found my own way.

You wrote some other adaptations of well-known modern works, like “The Male Animal” for Kraft and “The Last Tycoon” for Playhouse 90.

“The Male Animal” of course is based on a play by Thurber and Nugent. I don’t know if it’s based on a real-life story or not, but we updated it. It was twenty years old by the time we did it, the play, and we put it into the sixties or whatever time it was. This originally was the story of a professor who was threatened because he permitted his English class to read the Sacco letter, or Vanzetti, whichever one of them wrote the eloquent letter. Which in fact we know was not written by that fellow at all; I think it was written by Heywood Broun. But it did seem to me that it wasn’t reasonable, the fact that anybody would be disciplined for reading the Sacco letter in the sixties. So I asked my brother what we should do. He said, “What you do is, just make one change: Have this take place in a California college, and he be disciplined for not letting his class read the Sacco letter.” Which is true. We didn’t have “politically correct” then as an expression, but that’s what Frank was anticipating and he was absolutely right.

The production of “The Male Animal” was a disaster. Everything went wrong there. In fact, there was a certain amount of ill feeling. Bill Dozier was now a big executive at CBS, and they were having difficulty casting the wife. I came to work one day, to the rehearsal, and I said, “Did you cast the wife yet?” They said, “Yes, what do you think of Ann Rutherford? That’s who we’re using.”

Well, Rutherford was wrong for the part, and she was also Dozier’s wife. The only thing I could think of was a British music hall routine where two guys come out and hit each other with bladders, and one says, “Oy, I’ve got a riddle for you, Joey: Two guys apply for a job at the colliery and one of them’s had extensive experience in actual mining, and the other’s a student of mining and a graduate of Oxford. Which one gets the job?” And the other guy says, “Oy don’t know, who does get the job, Bertie?” Bertie says, “Gaitskill’s bloody nephew, that’s who gets the job.” Gaitskill being the minister of agriculture or whatever he was. And unfortunately when I said this I could see the producer signaling me to shut up, because Dozier was standing right behind me. And that caused a certain stir at the time.

Rutherford was all right, actually. It was that we just had bad luck. At the opening of it, Andy Griffith, who plays the professor, he’s suddenly remembered his wife’s birthday and he’s at the door with flowers and she comes and answers the door. She opens the door, the light falls on the flowers, and all the petals drop off [due to the intense heat]. In full view of the audience. I guess we didn’t have the lighting set up before that. [The dress rehearsal was] without the lighting, maybe.

And everything went wrong from there on in. I ran into Andy Griffith about ten years later in the parking lot of a market in East Norwich, Long Island, where I was living. He was sitting in a convertible, and I went over and said, “Andy, it’s been a long time since we’ve met.”

“It has indeed.”

I said, “What have you been doing all that time?”

He said, “Hidin’.”

That was, I think, the only one that really was a disaster.

How involved were you, as the writer, in the production of your live teleplays?

Well, one you thing you had to do, at least on the good ones, Playhouse 90 and Kraft and Philco, you were there through the rehearsals so that what didn’t work you could change right there. You [could] figure out if it was impossible to make the costume change in time for the second scene, so you’d have to rewrite it and put somebody else in the second scene or do something. You could determine experimentally if what you had written worked. The director would tell you, “I can’t do this.”

I had good directors. John Frankenheimer did “The Last Tycoon.” A good Last Tycoon, I thought. It was the only Last Tycoon I’ve ever known that did it as an incomplete story, which it is, because Fitzgerald died before he finished it. It just ended. There are some notes that Fitzgerald did on how he wanted it to end, but he was pretty far gone, I think, by then, and they don’t make any sense. Most people carry the story on beyond the point where Fitzgerald took it. He just arbitrarily ended it on a shot of the half-eaten hamburger which is left on the beach, and they have gone into the beach house. [The TV version] was very well reviewed, but now nobody knows it and nobody thinks that that’s the construction to be used. But I think it still is.

My Monroe Stahr was a great mistake. It was Jack Palance. It was the only thing that screwed us up. Jack Palance is a good actor, but he can’t play a Jew. But everyone else was fine. That was Lee Remick’s first television [appearance], and she, oddly enough, was able to tell me something I didn’t know, which was that the character of Cecilia was actually modeled on Budd Schulberg. Of course, if you think about it, it had to be. He was the producer’s son; it had just been changed [by Fitzgerald] to the producer’s daughter. And how she found that out was she had just finished working with Budd Schulberg on A Face in the Crowd.

Del Reisman, the story editor for Playhouse 90, told me that he tried to match up writers with story material that was uniquely suited to them, and this seems like a classic instance of that. I’m guessing he can take credit for hiring you to write that particular teleplay because you grew up around the movie business during the time Fitzgerald wrote The Last Tycoon.

Yes, I think so. I did know a little bit about [that period in Hollywood history]. I was probably the only writer around who had actually seen Fitzgerald in person. I never talked to him, but he hung around with my father a little bit. I remember seeing him when I was a kid, really, and all I remembered is he wore a white sweater that had the 1932 Olympic emblem on it. Maybe that was in 1932, or maybe he just wore it for a long time. But I saw what went on in the movie business.

Did you grow up in Los Angeles?

Yes, from the age of four on until I graduated from high school. Then I went to Columbia, but I spent the summers out here.

It dovetails with your interest in politics, of course, but I would say that the primary theme I see running through your work is the use of true or historical material for your stories.

To some extent, certainly. For Schlitz Playhouse of Stars I did an incredible story which was true, but it didn’t sound true, even when we did it. It didn’t sound true when it was brought to me, although I know it’s the truth, and there was no way to make it sound like it was. This was [about] a young fellow seeking the Republican nomination for the assembly in the district of Queens, or Brooklyn, who somehow was approached by the Russians, who then gave him a little bit of money to finance his campaign. He met with them every day on how he’s going to give up state secrets after he gets elected. These Russians are out of their goddamn minds – first of all, an assemblyman is not going to learn any state secrets. They’re confused. Maybe in Russia “state” means something else, it means the country. They didn’t understand that. They thought New York was an independent state, like Uzbekistan or one of those Russian states. But also, of course, he was running for the Republican nomination in a district that the Democrats could never carry, haven’t carried to this day. And he played along with them and involved the F.B.I. It was an interesting enough story, but I couldn’t believe that the Russians did that . . . . It was named after the guy’s name; he had an odd name. It sounded like a comedy and it wasn’t.

I did a great spy story that nobody seems to have told properly. Colonel [Rudolf] Abel was the greatest Russian spy that ever was, I think. What he did was he moved into New York, I guess in the forties, during the Cold War. He rented an apartment or a hotel room or something close to the Federal Building, and he ran a half-dozen spies who were his subordinates. He summoned them by putting a thumbtack into the big “no” sign in Central park, that said “No ball playing, no bike riding, no hunting, no this, no that.” According to where he put it, that said where the meeting was. Also he had his radio sender and radio receiver hooked up and stretched around a wire out the window over to the Federal Building, and he’s using federal power! This is what he’s going to send stuff to Moscow with, if he ever gets anything. Of course he doesn’t get anything, because there isn’t anything to be had and never was in any of these [cases]. Nobody ever really got a secret. The secrets in espionage are always the names of the other agents. That’s what you sell: you sell out all your undercover agents in Berlin or all the ones in Prague or something. But are they getting any information from any of these people? If you stop them, what are you stopping? Nobody knows what you’re stopping.

Then the Russians, incredibly, assigned an assistant to Abel named [Reino] Hayhanen, and the reason they assigned him to New York was because he was so drunk, perpetually drunk, that they wouldn’t trust him in Paris. They sent him to Abel, and he was very useless to Abel, but one day – Abel’s prize possession was a nickel which he had managed somehow to slice, insert a big hole in, and then screw back together, so that if he ever did get something he could microfilm it and that nickel could then be carried to Moscow and nobody would notice.

He left the nickel on his desk and Hayhanen, going to lunch, picked up the nickel and bought a Journal-American from a newsstand right in front of the Federal Building. And this nickel, apparently because of what Abel had done to it, didn’t feel right to the newsdealer. I always said a blind newsdealer, but I’m not sure that that’s really true. He threw it on the ground, and it split open in front of an FBI man who was coming out of the FBI office, who immediately grabbed Hayhanen, who gave up Abel in a split second, and Abel went to prison. They wanted to execute Abel but a Democratic politician went and defended Abel against the death penalty, and beat the rap.

Abel is the one who ultimately was exchanged for Francis Gary Powers, the guy who screwed up the U-2. And my lawyer, James Britt Donovan, did that exchange! He carried him over. It was one of those things where they met on the bridge, and he walked out there with Abel and then walked back with Francis Gary Powers.

Francis Gary Powers, of course, eventually became a weather helicopter operator here in Los Angeles, and died when he forgot to put gas in his helicopter and it crashed.

Did you actually turn that idea into a script?

I don’t think I wrote the end of it. I proposed it, but I don’t think I actually wrote it . . . . We had a series called On Trial, and I think I dramatized the lawyer who [defended Abel].

On Trial, in my opinion, was the first of the [great courtroom dramas]. It antedated The Defenders considerably, and it was going to do important points of law. We did start out with some important points of law, such as unfair competition and criminal libel, things that people really don’t know anything about. Then NBC told us that the only point of law that they were interested in was the law against killing: you’re not supposed to murder. So we did only murder stories after that.

But they got a couple of seasons out of that, I think. They didn’t call it On Trial after a while – they changed the name to The Joseph Cotten Show. Jo Cotten was a running lawyer; he was in modern clothes, even in the old courtroom. He was always the commentator.

So you were a regular contributor to the On Trial series?

Yes. As a matter of fact, how I got involved with it, I proposed that show in the first place at the behest of the American Bar Association, and they didn’t want it. Then I submitted it to some advertising agency, which you did in those days, and they didn’t want it either.

And then I read that Collie Young – Collier Young was a literary agent and also a good writer and independent producer – [had a similar project] that he and Ida Lupino were going to do together. Exactly my idea – not only my idea, but they were dramatizing the same obscure case that I had selected in my presentation. It was Holmes against the United States, which was a guy who was in charge of a lifeboat that was overloaded in a storm, and he . . . selected who was to be thrown over the side of the lifeboat. They threw all of the men over, except those who were [married]: do not separate man and wife, he said. So they threw over all the single men, maybe half a dozen single men. The crime that was involved in that was that the next morning they discovered a single man who’d been hiding in the bottom of the lifeboat, and as an exercise of absolute fairness they had to throw him over the side too, which they did. Then Holmes was tried for all this, for murder, in Philadelphia and he beat the rap. It was a very nice case.

When I found out that Collie Young and the Filmakers Company, which was him and Ida, was going to do this, I found a lawyer who would sue them on speculation and we sued them for several million dollars, which in those days was quite a [lot]; now, today, of course, that’s the minimum; you can’t do it for less. We wound up amalgamating the two projects.

Collie and I became friends, and were friends until his death after that. In fact, it was because of that that we did On Trial, we did a spook show called One Step Beyond, which incredibly enough up until a year or so ago I used to see [on television] at three o’clock in the morning, these primitive half-hour episodes that we made for about forty thousand dollars with name actors. We didn’t have anything else, just actors. We took whatever sets there were. But he also produced that, and then he produced Ironside. I wrote that pilot. We had a good relationship.

*

Profiles in Courage also told docudrama-type stories. It was based on the best-seller ghost-written under President Kennedy’s name, and vetted by people on his staff.

Yes, I think I wrote six of them. They were quite accurate. Ted Sorensen had to look at them, and he had to say, not that they were necessarily [factual], but that it could have been that way. He was the one, Sorensen, that said we had to have a scene to demonstrate that each person, each of these profiles in courage, gave up important careers on a point of courage. Like the fellow who cast the deciding vote against the impeachment of Andrew Johnson: people who have thrown their lives away in support of an act of courage.

We were supposed to do twenty-four of them. Well, there aren’t twenty-four [people] in American history that meet that standard, nowhere near that. Now we wound up doing profiles. Bob Saudek said, “What we’re doing is we’re doing profiles of people against whom no act of cowardice could be proven.”7

And we did. What was Ben Lindsey’s great act of courage? He founded the children’s court. Well, that’s not a great act of courage but we tricked it up so that it became a great act. On the other hand, Black Tom Corwin was a senator who voted against the appropriations for the Mexican War, even [against] bandages and medicine for the soldiers. That took courage. When they told him, “Well, what are you doing that for, you’re only one senator,” he’s the one who said, “Well, I have only one vote, and when I cast it I have to cast it as if I were casting the vote of the entire senate.” And he destroyed his political career with that one vote.

I’m trying to think of what the others were we did. Some of them were quite courageous – the guy who refused to execute the Mormons, General Doniphan. That was an act of genuine courage. He was the first person to say that when he took his oath to obey the orders of officers appointed over him, that meant legal orders. What his order was was to shoot the rebels, the Mormons, in the far west, in Nebraska. Well, the far west was their own headquarters; when they were able to penetrate that headquarters, the war was over. These were prisoners of war and he wouldn’t do it. And he got away with that. That’s the other thing, you could do profiles of people who got away with something.

You also did one on Frederick Douglass.

Yes. I think he was persistent rather than courageous. Yes, he did make speeches which exposed his own past and could conceivably have resulted in his being sent back to Baltimore to the fellow that owned him. But that never happened.

Did you choose the historical figures you wrote about?

I think we had a group of them, and I think I was permitted to say, “I don’t want to do this,” and “Let’s do something else.”

“Governor John M. Slaton,” with Walter Matthau in the title role and Betsy Jones-Moreland, was one of Mankiewicz’s Profiles in Courage segments that was not derived from President Kennedy’s book.

You wrote an episode of The Trials of O’Brien, a great New York-based drama starring Peter Falk as a schlubby but brilliant attorney.

Yes. The Trials of O’Brien is really, of course, Columbo. It doesn’t say so, but it’s exactly the same thing, the raincoat and the dog. The only thing that made it not work is that, unlike Columbo, O’Brien is divorced. You could not have a divorced hero at that time; it did not work. And the interplay between him and the ex-wife was what provided the comedy that kept the episodes going.

And you wrote one script for Star Trek.

Yes, a very early episode. My mind was distracted with other things, and I didn’t really finish it. They said they’d have somebody finish it and they did; another fellow, Steven Carabatsos, finished it. If I had been there I would have yelled about how they shot it. The only thing I specified was that the heroine could not be blonde. They made her blonde.

Why couldn’t she be blonde?

It just was out of character. This had to be a square lawyer, and they made her a ditzy blonde lawyer. And they changed a few other things. But I liked the piece; I thought he [Carabatsos] did a good job.

In a biography of Gene Roddenberry, the author reprints a memo in which Roddenberry wrote that your view of the future was too “pessimistic.”8

I didn’t think it was pessimistic. What I did was, I took their view of the [future], which was that everybody in this picture was electronic. You did research by button, like you do today, to some extent; everybody was hooked into Google. But this guy, the lawyer, who was [played by] Elisha Cook, Jr., a very good actor, he was the last person to have books. He looked things up, he pulled things down from the shelf, and they didn’t know what he was doing. But he won the case. Yes, if you think that’s a pessimistic view, that there would then be only one person with books, I think that’s what Roddenberry meant.

*

Then we come to a new phase in your career, in which you wrote the telefilm pilots for some long-running series at Universal.

Yes, Ironside and Welby, I did both of those for Universal. I still lived in New York. I did Ironside with Collie Young, and it worked. Then there was a producer named David Victor at Universal, and I think he was impressed by the fact that Ironside worked, and he sought me out somehow. He had been the producer of Dr. Kildare, and he wanted the same thing again. He wanted a young radical doctor and a conservative older doctor like they had in Dr. Kildare, and I must say I did solve that problem. I said, “No, you don’t want that. You want a young conservative and an old radical. Young fogie and old radical, that’ll work.” And it did work.

And that was Marcus Welby. Of course, today, you’d probably have a “created by” credit on both those shows.

I should have; I didn’t. I got diddled out of it. I should have had that on Ironside and Welby.

You kept writing for Ironside after the pilot.

A couple of them, yes. I think wrote the first episode, which I called “The Only Way to Beat the Horse Is With a Stick,” which I thought was a very good title. And they changed it to “Message From Beyond,” a standard title.

“Why did you change that?” I said.

They said, “It just seemed easier.”

I said, “Sure, because you already had that title made up [as an optical]. You didn’t have to shoot it again.” It was an Ironside involved with a crime at a racetrack.

There’s that horse racing motif in your work again.

Yes, I liked that. Well, my characters tend to go to the racetrack when they’re not doing [anything else]. Even Dr. Welby went to the racetrack. Only in one shot [in the pilot]. He went to the quarterhorses.

Horse racing isn’t as popular today as it was then, it seems.

Well, no. I don’t think people go to the races any more. You can follow it much better at home, and [if] you can maneuver the buttons on your phone you can bet ’em at home, which I do.

Collier Young was in essence forced out of Ironside early on, but you continued writing for the show under the new regime.

Well, they offered me a job as the producer, and in those days you would actually have had to produce it. It was around the time I was running for delegate, in 1966. I had to miss a session on the floor of the constitutional [convention] because I hadn’t seen it [Ironside]. I had to go somewhere and find a television set and watch it. And a close vote was held that night! It was lost because I wasn’t there, and the people who were pushing the vote were furious. I managed somehow to get another vote for them a couple days later, so that all was smoothed out.

That’s probably why I would not have agreed to produce it, because I was thinking too much of politics in those days. I regret that I didn’t do it. I could have stayed on producing stuff forever. It’s very easy. But I didn’t. I wanted to go back to New York.

Around that time you also did a made-for-television film called Who Has Seen the Wind?

That was an interesting project. The U.N. wanted to make a series of expensive movies and they wanted people to donate their services. Joe, my uncle Joe, did one, the Christmas one – Dickens at Christmas.9 These were all cast with only stars, many stars, a lot of money spent – but none for the writer. Joe volunteered his services and then suggested that I might want to do one. They talked to me and I said, “I’ll do one but I can’t do it voluntarily. I need the money.” And they gave me $10,000.

We had Gypsy Rose Lee, Edward G. Robinson, Stanley Baker, four or five other really big names that you never saw on television until that moment, doing it because it was for the U.N. It dealt with what are called stateless mariners after the war. They were people [who] got into a situation where they could never get off the ship, went back and forth [between ports]. I assume they got off the ship by now.

That’s the other problem with many of these films that relate to causes: once the cause gets satisfied, nobody wants to watch the film. More people would want to watch I Want to Live today if we still executed people with the gas chamber. But now it’s a period piece – what the hell is that? Did they ever do that? And this is true now that these people are back on dry land by now. I hope.

So you were very late among the migration of TV writers from New York to L.A.?

I think so. It just sort of occurred. I married Carol in ’72. We were still living in New York then. We used to come out here for most of the year. We didn’t move out here because as long as we maintained a residence in New York, all of our expenses out here were deductible, as if we were visiting the plant and staying at the Holiday Inn. Everything, haircuts, didn’t matter, all of this was deductible. And then after a while they . . . raised the question of whether I was really a resident of New York. In fact, I went to a hearing in New York, and the IRS said, “This man is in California for eleven months of the year, and he’s claiming New York as his residence.”

I said, “Well, I own a home. I don’t own a home in California, I own a home in New York. My driver’s licence is New York, my car is registered in New York, I vote in New York.”

The man said, “But you’re here in California for eleven months of the year.”

And then my tax accountant jumps up and he says, “Wait a minute, this man lives in New York. He is in California for eleven months. What month does he come to New York?”

Well, it turned out that the last couple of years I’d spent August in New York. He said, “Now, tell me, Harry, is it the position of the United States that this man really lives in California but he comes to New York in August for his vacation?”

And they said, okay, we’ll let it go, forget it. Very well done, I thought. I really admired that tax man.

Obviously you were not yourself blacklisted, but I would imagine that as a politician and a Hollywood veteran you were keenly aware of the blacklist and its effects.

My son John has a daughter who’s in a kind of elegant high school out in the Valley. It costs a goddamn fortune but it seems like a nice place. They asked if I would come out and talk about the blacklist, because I’m considered an authority on the blacklist. I don’t know why.

Because of your novel Trial?

I guess so, but they wouldn’t know that, these kids. Trial is one of the most obscure movies ever made today. Two or three years ago my wife was called to jury duty in Glendale, and it’s one of these ones where you have to call every night and if they need you the next day you have to go there. They needed her, and it was a nasty day when she went there and she really didn’t want to go back for the second day. She got put on a panel of about twenty from which a twelve-person jury was going to be selected. In the questioning, they asked the jurors to say what their occupations were and what their spouse’s occupations were. She said that she worked with old people, which she does – she’s an activities director at a very elegant old persons’ home.

“And what does your husband do?”

“He’s a writer.”

“Well,” says his defense attorney, “Has he written anything about the law, or courts, or anything like that?”

Now she couldn’t think of I Want to Live, which is really a courtroom drama, but she remembered Trial. She said, “Yes, he wrote a picture called Trial.”

The defense attorney said, “Trial? With Glenn Ford and Dorothy McGuire? That’s my favorite picture!”

She told me about that that night. She still had to go back the next day. I said, “Don’t worry, you don’t have to go.” I said, “One of two things could happen. Trial is the man’s favorite picture and he’s still [young enough to be] practicing law?” I couldn’t believe that, because Trial is not a picture like I Want to Live, [which] you might have seen years after it was made. You didn’t see Trial – it opened at Radio City and it had its run and that’s it. Unless it gets on Turner Classic Movies. They play it once a year on Arthur Kennedy’s birthday. They do that for dead actors.

And I said, “The other thing, aside from the fact that astonishedly he’s still alive, you will not be on that jury.” Sure enough, the first thing the next day, the district attorney challenged her. He didn’t want anybody in the jury whose husband wrote the defense attorney’s favorite picture! He didn’t have to know what the hell the picture was.

Trial was about blacklisting, but not in the motion picture industry. You, however, had good seats as the McCarthy era made its way through Hollywood.

My view on the blacklist . . . is not politically correct, because I believe the people who were blacklisted were no more talented than anybody else as a group. I agree with Billy Wilder that of the Unfriendly Ten, two were talented and the other eight just unfriendly. And I know which two he had in mind, I think: [Albert] Maltz and Sam Ornitz. Those were the only two there that I considered really talented.

Not Dalton Trumbo?

No. Trumbo was a hack, I think. Trumbo wrote what you asked him to write, and he was a good, competent writer, and it was outrageous for him to be blacklisted, or anybody, but he was not necessarily [a great writer]. That’s the other thing about the blacklist: how many of them would have been working without the blacklist? My father, having written Citizen Kane, could not get work after that for a period of time. He wasn’t precisely blacklisted; it was just [that] people didn’t want to hire him because he was unreliable, he drank, he said what he thought, particularly when he was drunk. When he was drunk, he insulted all the people that might otherwise hire him. Citizen Kane was not [yet] venerated. Today I think if you wrote Citizen Kane you could insult people the rest of your life and they would still let you work. But only because we’ve now discovered that was a really superb picture; we didn’t know at the time, we just thought it was an RKO picture that cost $800,000 and didn’t quite make the $800,000 the first time around.

Anyhow, how he lived was, we had rented a house on Tower Road, which today I would say cost easily $2,000,000, with a pool and a triple garage and an office over the garage, a porte cochere. We had that house rented for fifty dollars a month [from] a Canadian woman who could not raise the rent because she was incompetent, and the committee that was handling her affairs wasn’t interested. So he would rent that house out – I think he probably got $500 on it, paying fifty back to the lady, and live on the four-fifty, which you could easily do in those days. Then he had a nice little house on Scenic Canyon, where he and my mother lived. I might have stayed there a while, too.

He was at work one day on a spec script – he did write a script called Woman on the Rocks afterward which [was a] biography of Aimee Semple McPherson, somewhat fictionalized – and he’s working away and one day the doorbell rings. And of course, being a writer, he’s going to answer the door because if he doesn’t answer the door he’s going to have to be writing. I understand that personally; I answer the door, every time. It’s better than facing an empty page.

So he goes to the door. Here’s a fellow who comes in and introduces himself and says, “Mr. Mankiewicz, I’m part of a committee and we’re raising a fund to help Lester Cole. You know Lester has been blacklisted?”

My father says, “Yes, that’s true. How much work did Lester have before he was blacklisted? Not very much, huh?”

“It doesn’t matter,” says the man. “You shouldn’t blacklist a man. He should have been given the freedom to pursue his career.”

My father says, “You’re absolutely right. Now I’ve written about forty features, which is probably ten times as many as Lester, and nobody seems to want to give me work. Is there any thought of getting up a committee for me?”

And the man said, “No, Mr. Mankiewicz, I don’t think there is because the difference is your problem is not political.”

My father said, “Oh, I think what you’re telling me is that there will be a committee for Lester Cole but not for me because Lester Cole is subversive.”

The man said, “Well, I wouldn’t put it quite that way.”

My father said, “Well, I would. I’d put it that way.” He said, “Let me tell you something, young man. If you could see into my secret heart of hearts, you would think Lester Cole is a patriot. Good day to you, sir.”

But he considered himself, and he was, probably more [of an anti-authoritarian]. He was against whatever was in power, whereas Lester Cole would not have been against it all the time. If his communists ever came to power, he [Cole] would have been for them. But he didn’t have much in the way of credits, and neither did the one that fought in Spain – Alvah Bessie. That was really basically his destiny; that was what made him a celebrated writer, that he fought in Spain. John Lardner, who had better credits, was killed in Spain.

My own views are basically that the whole thing of the blacklist was intolerant sons of bitches seriously mistreating and persecuting other intolerant sons of bitches. It should not be; the evil entirely was on the side of the blacklisters, no matter what these people did.

Were you ever tempted by radical views yourself, or did you share your father’s iconoclasm?

The story of my own involvement was: I was young, I was sixteen and in high school, and I thought, “I should do something to prevent the Nazis from taking over the world,” which it looked like they were going to in 1938. I joined the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, which my father said was all right to do. “They’re not communists,” he said, “’cause Oscar Hammerstein and Philip Dunne are in that, and they’re certainly not communists.” Okay. I joined.

A lady whose name I’ve deliberately forgotten and will never remember suggested to me, would I like to do undercover work? You ask a sixteen year-old boy to do undercover work on behalf of a cause that he believes in, you couldn’t keep him away with a stick. Of course I want to do that! So I joined, at their behest, William Dudley Pelley’s Silver Shirts. They arranged it and told me how to do it somehow; I don’t remember the details. It was a fascist group who, according to Pelley – who I believe was a retired general of some kind – would become essentially the same as Hitler’s Brown Shirts. They would take over the streets and beat up people and so on.

They met in a hotel on Figueroa. Very spooky and scary. There were about ten of them, and they were roughly the equivalent of today’s skinheads, except they didn’t shave their heads. They were mean, nasty kids, and I was scared. And I began to become increasingly scared of the ten of them, even though my father assured me that I was perfectly safe because probably half of them were plants [by other leftist or government organizations]. Primarily, I was fearful that they would find out that I was a plant and that I was not who I claimed to be. To go down to 10th and Figueroa or wherever this was, you needed a car, and I borrowed my father’s car for this. One of the hazards was that, in California in those days, you had to have the registration in a plastic thing that was wrapped around the steering post. It was easy for them to find out who owned that car; I had to park it near the meeting. So I told them that my father was a chauffeur who worked for some Jew in Beverly Hills who said, “Oh, you can borrow the Jew’s car,” so that if they found that name it wouldn’t be too bad. But they were getting closer all the time to unmasking me, and I finally got scared to the point where I didn’t want to do it any more. I went to my control one day after a particular meeting which I really was sure they were onto me and were just seeing how far I would run before they would take me out and beat me up. I said, “I don’t want to do this any more. It’s too dangerous.”

She said, “Well, actually it’s funny that you would ask, because you don’t have to do it any more. You don’t have to do it; nobody’s going to do it.”

I said, “Why not?”

She said, “Well, we’re not going to penetrate that sort of organization any more.”

I said, “I don’t understand.”

She said, “You haven’t seen this morning’s paper?” She showed me the paper, and it said that the night before at seven o’clock – I had not seen the blueline edition of the Times that night – the Hitler-Stalin pact had been signed. Now they’re not going to do this any more, the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League. She said, “Actually, we’re going to have to change our name. We’re going to be the Hollywood League Against Foreign Fascism.”

I said, “That’s very interesting. Where do I go to resign?”

And she told me about the membership secretary, and she said she’s very busy this day because a lot of people are resigning. So I went and got in line and resigned.

In the end the Communists took it over. They booted Oscar Hammerstein out, and they chased Philip Dunne away. Emmet Lavery, I believe, was in there too, and they got rid of him. The whole problem was, the battle was not between the right wing and the left wing, it was between the reformers – today they would be called liberals – and the radicals. They are natural enemies. Reformers want to improve the system, and radicals want to destroy it. It’s always been that way.

Notes

1 See John Frankenheimer: A Conversation with Charles Champlin (Riverwood, 1995), p. 34.

2 Gordon Cotler (1923- ) wrote the novels The Bottletop Affair and Arabesque, both of which were turned into feature films (the former under the title The Horizontal Lieutenant). Most of his television work was in collaboration with Mankiewicz, though Cotler did write the teleplay for The Facts of Life Down Under (1987) and several other made-for-television movies on his own.

3 It is unclear whether the Schlitz Playhouse episode “Never Wave at a WAC” is related to the film of the same title, which starred Rosalind Russell and was released the following year. It is possible that Mankiewicz’s jewel thief summary refers to a different teleplay.

4 Felix Jackson (1902-1992) was a German screenwriter who emigrated to Hollywood, married Deanna Durbin, and produced movies at Universal in the forties. The final phase of his unpredictable career was as a producer of live dramatic anthologies in New York, chiefly the 1953-1956 seasons of Studio One (which included Reginald Rose’s “Twelve Angry Men”).

5 Don’s distinguished younger brother Frank Mankiewicz (1924- ) was Senator Robert Kennedy’s press secretary and later the president of National Public Radio. He managed George McGovern’s 1972 presidential campaign and occupied a slot on Nixon’s enemies list.

6 Charles Schnee (1916-1963) had screenplay credits on Red River (1948), They Live By Night (1949), and The Bad and the Beautiful (1952). As a producer at MGM in the late fifties he also oversaw Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956).

7 Theodore “Ted” Sorensen (1928- ) was President Kennedy’s primary speechwriter, and his ghostwriter on the book Profiles in Courage. Robert W. Saudek (1911-1997), the executive producer of the Profiles in Courage TV series, was a tireless advocate for quality television best known for producing the cultural affairs series Omnibus in the fifties.

8 See Joel Engel’s Gene Roddenberry: The Man and the Myth Behind Star Trek (Hyperion, 1994), p. 90-91.

9 The fascinating Carol For Another Christmas (1964) was a television special with an anti-war theme, based on Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Joseph L. Mankiewicz directed the teleplay by Rod Serling. Like Don Mankiewicz’s subsequent Who Has Seen the Wind?, it featured an all-star cast including Sterling Hayden, Peter Sellers, Robert Shaw, Eva Marie Saint, and Ben Gazzara.

All Text and Interview Copyright © 2007 Stephen W. Bowie